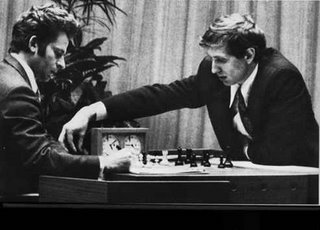

Brooklyn Boy Fights Cold War on Chess Board!

During the Summer of 1972 it seemed like every New Yorker was caught up in

the fervor surrounding local boy Bobby Fischer's battle to win the world

chess championship from the Russians, who had held it since World War

II. The best-of-24-games match, which was held in Iceland, was not only a

metaphor for the Cold War, but also resulted in a huge interest in in chess

amongst the public. It was like a Subway Series, the Olympics and the

Ali/Frazier fight, all rolled into one.

Chicago native Bobby Fischer became a chess prodigy after moving to NYC,

where he attended the prestigious Erasmus Hall High School in Flatbush, and

by 1972 he was ready to take on Boris Spassky, Russia's best. To understand

the competition in its context, it helps to remember that chess is not a

game in Russia; it is, as P. J. O'Rourke pointed out, a spectator sport.

And the Soviet Union's leadership made certain that only winners went on

to represent their nation on the worldwide circuit, thereby proving the

intellectual superiority of their ideology. Consequently, this was going to

be more than just a chess match.

Alas, Fischer turned out to be no nice Jewish boy from Brooklyn. At the

last minute he refused to travel to Iceland until the promoters put up

substantially more money for the tournament. Something of a recluse, he

would he heard in his hotel room rehearsing moves, yelling things like

"Pow!" when he captured a piece, and he would insist upon having the

swimming pool all to himself. But the public was willing to forgive Bobby

(at least at the time) for the sake of Old Glory. The media was caught up

in the excitement, and you could watch live coverage of the tournament on

television, including expert commentary. Since quite a few minutes could

often pass between moves, such programming was not exactly fast-paced. You

could also catch up on the day's developments on the evening news, and the

papers would list every move.

Sales of chess sets in many strange styles boomed. There was one set which

glowed under "black" light, and another in which the pieces were made from

nuts and bolts. It seemed as if everyone was playing, and you could see

games everywhere: on stoops, atop milk crates and in pizzerias. It was

really a grassroots movement.

Spassky resigned the tournament on 9/1/72, and Fischer came home an

American Hero. He wrote books on chess and remained active in the sport for

years, as did his opponent. With time, however, the Erasmus alumnus showed

himself to be even wackier than we had thought.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home