Why Did Tricky Dick Increase Welfare?

Sounds like an odd combination; doesn't it? Welfare and Nixon. Yet, on January 1, 1974, millions of elderly, blind and disabled Americans found something new in their mailboxes: checks from Uncle Sam for up to $250. What's more, Tricky Dick was allotting millions of dollars to state and local governments for various medical and other services for them. What was up? Did the infamous "nut cutter" have a soft spot for the sick and old?

The answer is a little more complicated. The checks I just mentioned came from the new Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program, administered by the federal Social Security Administration. Prior to that time, aged and disabled Americans who didn't qualify for much in terms of Social Security benefits could get additional grants through their local welfare departments, using money allotted as part of the Social Security Act. At the same time, the federal government was also spending millions on its "War on Poverty," sponsoring programs like Head Start, the Job Corps, etc. The local welfare programs and the anti-poverty programs had one thing in common: they employed lots of social workers. And Nixon disliked social workers, the way he disliked most of what he considered the educated elite.

Nixon put jurisdiction for supplemental benefits for the elderly, disabled and blind under the Social Security Administration, a vast federal agency with no experience in administering welfare programs. Social Security, let us remember, was designed as a form of insurance. The initial situation was a mess. At one Social Security office in Brooklyn so many people showed up to report not getting their checks that the agency rented busses to serve as waiting rooms. And some of the new program's rules were positively riddiculous. Still, Nixon had found himself in alliance with a lot of welfare advocates. He didn't like bureaucrats, and neither did they. Social Security essentially doled out the money on an honor system. But it was cheaper, Nixon believed, to just print checks than to pay investigators and worry about things like job training programs.

The related block grants to state and local government were another illustration of Nixon's philosophy. Unlike Johnson, who saw the Federal government as having an active role in defeating poverty, Nixon simply gave money to the states to spend their own way. Again, less bureaucracy. Fewer social workers. Such "outsourcing" of government programs was to become a major feature of other presidencies in the next deccade.

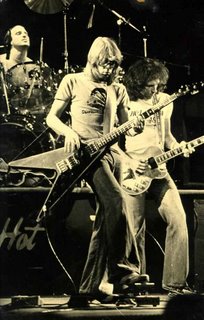

The Hot ########Tuna! Phenomenon

Some guys have all the luck. Consider Jorma Kaukonen and Jack Casady, the backbone members of Hot Tuna:

- They got almost no airplay on any station.

- They never had a hit.

- Lots of people couldn't pronounce Jorma's name right.

- They never went along with any musical fads.

- Their album covers were some of the strangest you'd ever find.

Yet Hot Tuna were hugely popular, especially amongst working-class kids from the outer boroughs, and they consistently sold out just about every show they played.

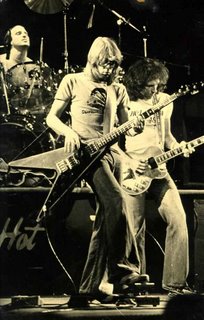

Jorma and Jack achieved fame during the 60s for their role as lead guitarist and bassist, respectively, of a certain West Coast band that did a lot of songs about drugs and other topics that won them the ire of our elders. But even after they would be worn out from doing shows with Jefferson Airplane, these two would often continue playing, in hotel rooms, clubs, etc. Their material was mostly blues, with a bit of country and other American roots styles tossed in. In 1970 their first album, entitled simply "Hot Tuna," was released. It consisted of lots of blues standards like "Death Don't Have No Mercy" and "Know You Rider," with Jorma on acoustic guitar and vocals, Jack on bass and Will Scarlet helping out on harmonica. The band reportedly chose their name because RCA wouldn't let them use their first choice "Hot Shit."

often continue playing, in hotel rooms, clubs, etc. Their material was mostly blues, with a bit of country and other American roots styles tossed in. In 1970 their first album, entitled simply "Hot Tuna," was released. It consisted of lots of blues standards like "Death Don't Have No Mercy" and "Know You Rider," with Jorma on acoustic guitar and vocals, Jack on bass and Will Scarlet helping out on harmonica. The band reportedly chose their name because RCA wouldn't let them use their first choice "Hot Shit."

Eventually Jorma and Jack left the Airplane (hereafter known as Jefferson Starship) and recorded more albums. Jorma switched over to electric guitar, and they were joined by drummer Sammy Piazza and famed fiddler Papa John Creech. Jorma's fingerpicking style, which involved a lot of heavy thumb work, was influenced by the Reverend Gary Davis, a blues master. As for Jack, he sounded a lot like, well.... Jack. In truth there has never really been a rock bass player like him. Jack never seems to have played a pattern, yet his timing was solid, and he could groove like few others. Few rock bassists had such loyal followings, and crowds would cheer when he would solo during tunes such as "Funky Number Seven."

the Reverend Gary Davis, a blues master. As for Jack, he sounded a lot like, well.... Jack. In truth there has never really been a rock bass player like him. Jack never seems to have played a pattern, yet his timing was solid, and he could groove like few others. Few rock bassists had such loyal followings, and crowds would cheer when he would solo during tunes such as "Funky Number Seven."

As time went on, Hot Tuna got louder, although Jorma and Jack would still sometimes perform simply as a duo, with Jorma on acoustic guitar. In this sense, they pre-dated the "Unplugged" movement by years. "Acoustic Hot Tuna" and "Electric Hot Tuna" were very different, although most of us enjoyed both. In  NYC they would typically play the Academy of Music on 14th Street, just east of Union Square, playing two shows a night, one at 8:00 and the other 11:30. Hard core Tuna fans usually chose the latter, since without time constrictions Jack and Jorma would often play four-hour continuous sets - followed by up to three encores. It was obvious that these guys loved to play, and their dedication to their music, without a lot of BS, was a refreshing thing in an era of hype and glitter. One night, when my brother and I didn't come home by 5:00 AM, my mother called the police. The desk officer assured her "Lady, we get lots of calls from parents when Hot Tuna plays."

NYC they would typically play the Academy of Music on 14th Street, just east of Union Square, playing two shows a night, one at 8:00 and the other 11:30. Hard core Tuna fans usually chose the latter, since without time constrictions Jack and Jorma would often play four-hour continuous sets - followed by up to three encores. It was obvious that these guys loved to play, and their dedication to their music, without a lot of BS, was a refreshing thing in an era of hype and glitter. One night, when my brother and I didn't come home by 5:00 AM, my mother called the police. The desk officer assured her "Lady, we get lots of calls from parents when Hot Tuna plays."

Jorma an d Jack continue to play to this day, both together and in solo acts, and Jorma operates a well-known guitar camp.

d Jack continue to play to this day, both together and in solo acts, and Jorma operates a well-known guitar camp.

When I recently told a friend that I had been a Hot Tuna fan she laughed. I'm not sure why; maybe she thought that it was akin to following the Bay City Rollers. As someone who grew up on pop music, I wouldn't be surprised to hear that she never even heard Jorma and Jack. If so, even she would be forced to agree that these guys helped turn more of us on to real blues than any other band.

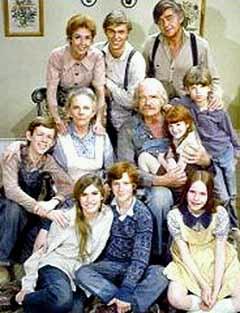

The Waltons: American Mythology

As I've said before, most of the major movements during the Seventies were accompanied by strong counter-movements. In the world of pop culture, the increasingly risque world of television was also accompanied by the rise of some of the corniest stuff to come out since "Father Knows Best." Probably the best example of this was the series "The Waltons," which aired on CBS from 1972 to 1981. If anyone needed proof that Americans were yearning for a return to their mythological, wholesome frontier days (which didn't really exist) this was it. Earl Hammer Jr., the author whose works formed the basis for the series, was a sociological genius; he spotted this trend years before the Neo-Cons with their focus groups and surveys.

As I've said before, most of the major movements during the Seventies were accompanied by strong counter-movements. In the world of pop culture, the increasingly risque world of television was also accompanied by the rise of some of the corniest stuff to come out since "Father Knows Best." Probably the best example of this was the series "The Waltons," which aired on CBS from 1972 to 1981. If anyone needed proof that Americans were yearning for a return to their mythological, wholesome frontier days (which didn't really exist) this was it. Earl Hammer Jr., the author whose works formed the basis for the series, was a sociological genius; he spotted this trend years before the Neo-Cons with their focus groups and surveys.

"The Waltons" had its birth in a TV movie called "The Homecoming," which aired in 1971. CBS took a gamble on a series based on the flick, and it paid off. John and Olivia Walton and their seven kids were a family so squeaky clean that Disney himself could not have created them. The series depicted their hard lives in the Blue Ridge Mountains, frequently narrated by eldest son John, Jr., aka "John-Boy," who wants to be a writer. We see Ma and Pa Walton dealing with the Depression, World War II and other trials that test their resilient PVC souls, with the characters changing over the course of the years. In this sense the series was interesting, as viewers could watch the Walton clan marry, have kids, etc. Olivia Walton, the matriarch, was a very devout woman who seemed to always be in church, or talking about it (at least in the episodes that I saw), while Pa was one of those strong, righteous types celebrated in Westerns. Every episode ended the same way, at night, with one light on, as everybody says goodnight to everyone else, a process which seems to take forever.

To its credit, "The Waltons" was really not a bad show, and the writers certainly did not have to resort to vulgarity to get viewers. What I found so strange, and often irritating, about the series (which my parents loved) was how so many people wanted to believe that people like the Walton family existed. It also illustrated well the traditional view of rural life as good and righteous, perhaps as a counter-balance to what people thought was happening in the cities. True, things like murder, teen pregnancy and other things often associated with urban decay were really much more common in the rural "Bible Belt," but so many of us chose to forget that - at least while the show was on.

Bachman-Turner Bickering

The four fat guys who powered the Bachman-Turner Overdrive hit machine didn’t smoke, drink, use drugs or chase groupies. Still, their oh-so-clean lifestyles didn’t mean that the boys always got along. Just as with Creedence Clearwater Revival, BTO’s road to stardom ended with squabbling and lawsuits.

The four fat guys who powered the Bachman-Turner Overdrive hit machine didn’t smoke, drink, use drugs or chase groupies. Still, their oh-so-clean lifestyles didn’t mean that the boys always got along. Just as with Creedence Clearwater Revival, BTO’s road to stardom ended with squabbling and lawsuits.

Guitarist/songwriter Randy Bachman was a veteran of The Guess Who, one of Canada’s best-known bands. Not approving of the group’s lifestyle, he left in 1970 and formed Brave Belt with his brothers Tim and Robbie, as well as bassist Fred Turner. After two largely unsuccessful albums, they changed their name to Bachman-Turner Overdrive after seeing the masthead of a truckers’ magazine. After some 25 other record companies refused them, Mercury (who also booked the New York Dolls) signed with BTO, and their first album with the new label was hugely successful, thanks partially to the group’s extensive touring. Their first hit, “Taking Care of Business” was actually penned by Bachman during his Guess Who days, with the title “White Collar Worker,” but never went anywhere. But now it was almost an anthem. The public loved BTO’s hard-driving sound, humorous lyrics and catchy melodies. During a turbulent time, these guys were actually a clean, but serious, rock and roll band - not some bubble gum act. Tim Bachman left after the first album, and was replaced by guitarist Blair Thornton.

Behind the scenes, however, things were starting to get nasty. Do a web search on the band or its members and you’ll encounter many different stories about who did what  to whom, with bitter feelings on both sides, but it appears that the major conflict emerged over Randy Bachman’s increasing role in writing and producing their material. Turner became so angry that on one album cover he insisted that his picture be shown in profile – since he believed he wasn’t fully involved in its production. Randy finally quit in 1979. Lawsuits followed over who had the right to use the BTO logo, and there were even arguments as to who sang on what records. The remaining members still tour under the name “BTO,” while Randy currently has a show on CBC radio and plays with Guess Who vocalist Burton Cummings.

to whom, with bitter feelings on both sides, but it appears that the major conflict emerged over Randy Bachman’s increasing role in writing and producing their material. Turner became so angry that on one album cover he insisted that his picture be shown in profile – since he believed he wasn’t fully involved in its production. Randy finally quit in 1979. Lawsuits followed over who had the right to use the BTO logo, and there were even arguments as to who sang on what records. The remaining members still tour under the name “BTO,” while Randy currently has a show on CBC radio and plays with Guess Who vocalist Burton Cummings.